Don't tell me what to feel! Show me.

A lesson in empathic design from Steve Martin and Martin Short

Last Friday, I felt a scratch at the back of my throat. By Saturday, I’d started sneezing. By Sunday, I was sore and feverish.

The prescription for the virus was clear: lots of rest, plenty of fluids, and a binge-worthy boxset to see me through my convalescence.

While I’ve been enjoying The Last of Us and Succession lately, virulent fungus and corporate backstabbing weren’t quite the medicine I was looking for in my condition. So instead, I turned to the tried and tested remedy of Steve Martin and Martin Short.

Their latest collaboration, Only Murders in the Building (available on Disney+ in the UK and Hulu in the US), focuses on three residents of a New York apartment complex, who are brought together by a shared love of true-crime podcasts. When another building resident dies in mysterious circumstances, the trio team up to create their own podcast and crack the case.

Every episode of the first season is tightly scripted, well-acted and very funny. But there was one that stood out to me. Episode 7 – ‘The Boy from 6B’ – is primarily presented from the perspective of Theo Dimas: a deaf resident of the building. Accordingly, there is no audible dialogue in the episode. On the rare occasions when characters communicate directly with one another, their words are relayed to the viewer through subtitles, as Theo interprets American Sign Language (ASL) or reads lips.

For a show whose appeal is rooted in the witty repartee of its protagonists, the effect is intentionally jarring.

In an interview with the LA Times, show-runner John Hoffman describes pitching the episode to executives at Hulu and 20th Century:

There was a very gentle conversation creatively with the executives: ‘But we’re still going to hear that dialogue, right?’ I said, ‘No, the audience will need to be paying attention and looking at the television screen. I know that’s a radical thought — right now, everyone’s multitasking on phones — but that is the leap I’m hoping you’re willing to take.’

The additional effort the episode demands of the viewer reflects Theo’s own experience in the show. Through his eyes, we see the frustration and confusion others encounter when attempting to communicate with him. And we share Theo’s feeling of isolation that results from this.

While I enjoyed the episode and admired its ambition, I was almost relieved when it was over. And I think that’s kind of the point.

Hoffman wanted his audience to take a ‘leap’ to empathise with Theo and experience the world from his perspective. Had he taken a different approach, I doubtless would have left it feeling differently about the character. I probably also wouldn’t still be thinking about this episode one week later.

As learning professionals, we’re often tasked with creating experiences that will have a similar impact on learners. Whether we’re designing materials to support a DE&I initiative, scoping a programme on disability awareness, or developing vulnerable-customer training, we’re not only concerned with what we want learners to know or do. We’re also concerned with what we want them to feel.

In each of the preceding examples, one of our primary objectives might be encouraging learners to empathise with someone whose lived experience is very different to their own.

So, how do we do that?

In a recent DE&I project with Burberry, we approached this issue by creating a choose-your-own-adventure experience, where learners had the opportunity to explore scenarios through the eyes of different characters. Unlike a conventional choose-your-own-adventure game, the outcome of each scenario was determined not only by the choices the learner made, but by the character they selected. This was based on factors including race, gender, sexuality, and physical appearance.

Just as John Hoffman could have simply told us what Theo’s life was like through exposition, we could have simply told learners that identity matters at Burberry. But like Hoffman, we wanted our audience to take a leap. We wanted them to feel it.

Want help designing memorable, emotive learning experiences? Get in touch by contacting: custom@mindtools.com (or hit reply if you’re reading this in your inbox!)

🎧 On the podcast

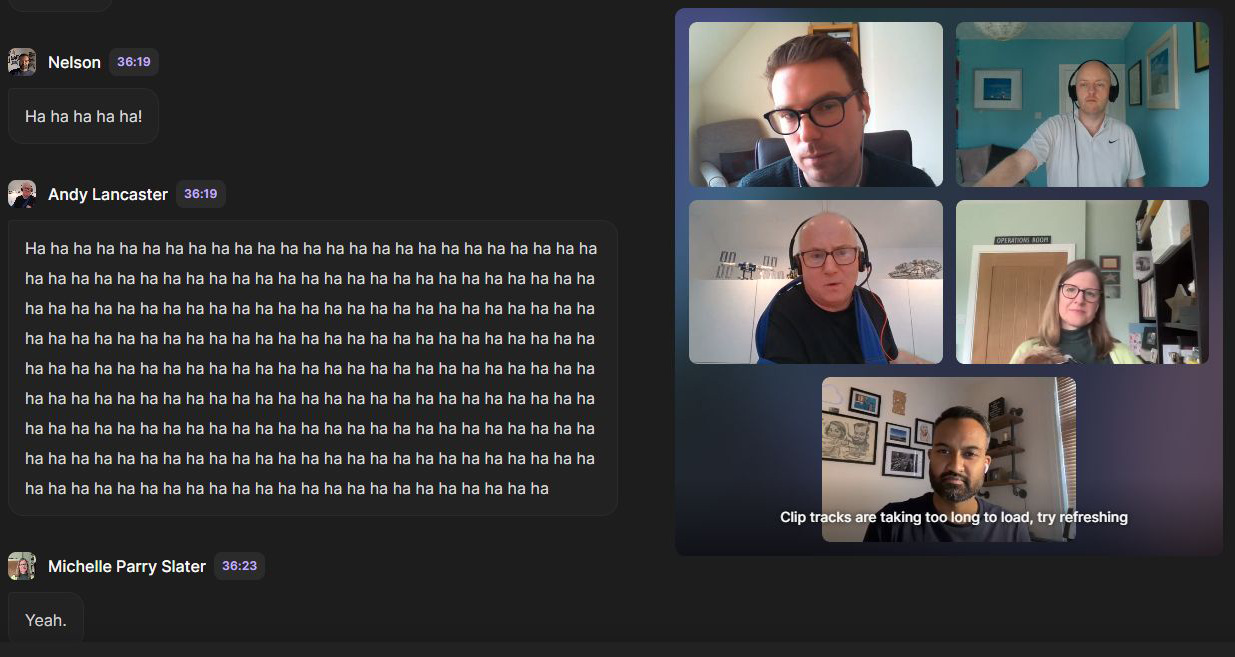

Over the years we’ve covered some great L&D books on the podcast, but we’ve never taken the time to ask how they get written. In this ‘roundtable’ episode, authors Andy Lancaster, Nelson Sivalingam, Michelle Parry-Slater and Gary Cookson join Ross G to share their insights.

And they provide some inspiration for those of you out there who are thinking of writing a book!

Here’s just a sample of the conversation, generated by our recording platform’s AI transcription service:

For further LOLZ, check out the full episode below:

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, Spotify or the podcast page of our website. Want to share your thoughts? Get in touch @RossDickieMT, @RossGarnerMT or #MindToolsPodcast

📖 Deep dive

Recently, I’ve been working with a client on a ‘test-out’ approach to compliance training. The idea of a test-out is simple: rather than asking learners to plod through the same suite of courses every 12 months, you test what they remember by assessing them upfront. If they get a question right, they proceed to the next one. If they get it wrong, they’re presented with corrective feedback, adapted from the original course.

When discussing this strategy with the client earlier this week, she recommended I read ‘Learning from Errors’, a paper by Janet Metcalfe, published in the Annual Review of Psychology. The paper argues that, while a lot of education is focused on the avoidance of errors, this approach may be counterproductive, at least for neurologically typical students. Metcalfe writes:

‘Experimental investigations indicate that errorful learning followed by corrective feedback is beneficial to learning. Interestingly, the beneficial effects are particularly salient when individuals strongly believe that their error is correct: Errors committed with high confidence are corrected more readily than low-confidence errors. Corrective feedback, including analysis of the reasoning leading up to the mistake, is crucial.’

‘I already know all this’ is a common learner complaint when it comes to compliance re-certification. Maybe they do. But, if they don’t, getting them to make high-confidence errors might be the best way to correct their behaviour.

Janet Metcalfe. (2017). Learning from Errors. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol 68, pp 465-489.

👹 Missing links

🧑🏾🤝🧑🏻 Turns out 'empathy' is pretty new, and maybe it's already had its day

I used the word ‘empathy’ a lot in this week’s issue. But what do you think empathy is? Understanding how another person feels? Feeling what they feel? Feeling that so strongly that you act? In this post, Tom Spencer argues that the word 'empathy' has been weaponised and that it might be better to say 'connection' or 'compassion'. It's a thoughtful piece, and worth a read if you want to empathise with his position.

😎 The difference between self-confidence and self-efficacy

Another project I’m working on focuses on developing learners’ negotiation skills. Following a literature review of effective approaches to negotiation in L&D (shoutout to Gent from our Insights team!), we discovered that learner ‘self-efficacy’ was correlated with successful negotiation outcomes. ‘Self-efficacy’ sounded a lot like self-confidence to me, but it turns out there’s an important distinction, neatly explained in this LinkedIn article by William Price. Whereas self-confidence describes a general strength of belief, self-efficacy refers to task-specific expectations the learner has about their abilities in a given situation - like negotiating a deal.

📰 The Metaverse is quickly turning into the Meh-taverse

As I wrote in a previous edition of the Dispatch, I’m still pretty keen on the idea of the metaverse, but it’s clear the initial shine has come off for businesses and investors. In this article from The Wall Street Journal, Megan Bobrowsky reports that Disney and Microsoft both axed metaverse-related projects in the last month. This isn’t to say they’re abandoning the technology entirely, but it’s fair to say that AI is the party everyone wants to be at.

And finally…

For further evidence that telling your audience something is less effective than showing it to them, check out this old sketch from Stephen Colbert and Bryan Cranston.

👍 Thanks!

Thanks for reading The L&D Dispatch from Mind Tools! If you’d like to speak to us, work with us, or make a suggestion, you can get in touch @RossDickieMT, @RossGarnerMT or email custom@mindtools.com.

Or hit reply to this email!

Hey here’s a thing! If you’ve reached all the way to the end of this newsletter, then you must really love it!

Why not share that love by hitting the button below, or just forward it to a friend?