Even a child can solve your workplace learning analytics challenges

A lot of L&D folks aren't comfortable with numbers. Don't worry about it.

Last week I had the privilege of speaking at E-Learning Fusion in Poland on the topic of ‘designing high-impact digital learning’. I spoke for about 20 minutes, but I can sum up the session in just a few words: If you do not know what you are trying to achieve, you cannot tell if you had an impact.

This might sound like an incredibly obvious statement but, in our work with stakeholders around the world, we find that rushing to a ‘solution’ is common.

It’s easier, after all, to create a piece of training than to understand what’s gone wrong in the first place.

In the biz, they call that ‘solutioneering’.

In Poland, the CIPD’s Andy Lancaster posed an alternative approach. He introduced key consulting questions, based on common frameworks, that learning teams can use to dig deeper into the problems they’re trying to solve.

Nazaré’s Wil Procter then introduced the Strategyzer Test Card as a useful tool to hold ourselves accountable - and pointed out that most of the math required by a learning professional could be completed by a child.

(This claim about the level of math required is bold and I’ll return to it later.)

In the meantime, let’s tie our three sessions together. I’d say that I provided a high-level overview of why defining a problem is crucial; Andy covered how to define that problem; and Wil covered how to measure the change.

None of this is as difficult as it sometimes seems.

Let’s look at an example.

The problem

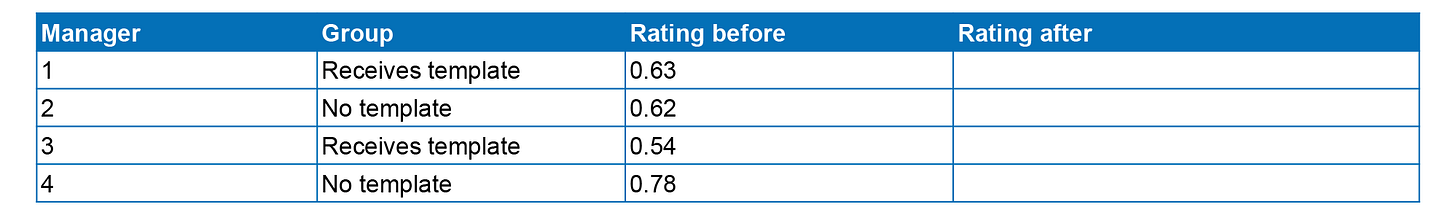

Your organization runs a colleague engagement survey twice a year. The survey presents a series of statements, like: “My manager gives me useful feedback on how well I am performing” (taken from CultureAmp). Colleagues respond with ‘Strongly agree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Disagree’ or ‘Strongly disagree’.

Across your business, the average score for this question is 0.67 (67%). You know that feedback is crucial to improving performance, and so you think that this is too low. It looks like managers are not giving enough useful feedback to their teams.

At this point, you start recording some information:

The deep dive

Because you buy into the idea that we shouldn’t rush to produce training, you ask some of Andy’s performance consulting questions.

Questions like:

Is the problem simple or a symptom of a more complex issue?

Is this about knowledge, skills, motivation or environment?

What would be the risk if we did nothing?

The answers to these questions help you determine whether the problem is worth tackling, and what the solution might be.

In this case, let’s say that the solution you identify is a ‘Giving feedback’ template. This will be sent to managers once a week with an encouragement that they use it with at least one member of their team.

The experiment

Now you want to know if your template actually has an impact. In other words, does it work? Does it improve the quality of feedback that managers give their direct reports?

Here’s a way to test this: We send the template on a weekly base to the same randomly-selected group of managers. Then, when we re-run the engagement survey, we compare results for those who received the template with those who didn’t. This is what’s known as a randomized controlled trial.

We can use this information to populate the Strategyzer Test Card:

Step 1: Hypothesis. We believe that… our ‘Giving Feedback’ templates will lead to better feedback from managers.

Step 2: Test. To verify that, we will… randomly assign managers to Group A and Group B, and only provide the workshop to Group A.

Step 3: Metric. And measure… the change in engagement survey results for our questions about feedback.

Step 4: Criteria. We are right if… direct reports for managers in Group A score their managers higher on giving feedback than the direct reports for managers in Group B.

The data

Our Test Card now tells us the additional data we need to collect for each manager: Which group they are in and the rating they receive after our experiment.

Let’s add these details to our table:

Look at those empty cells at the end. As Wil pointed out in Poland: They’re begging to be filled.

The results

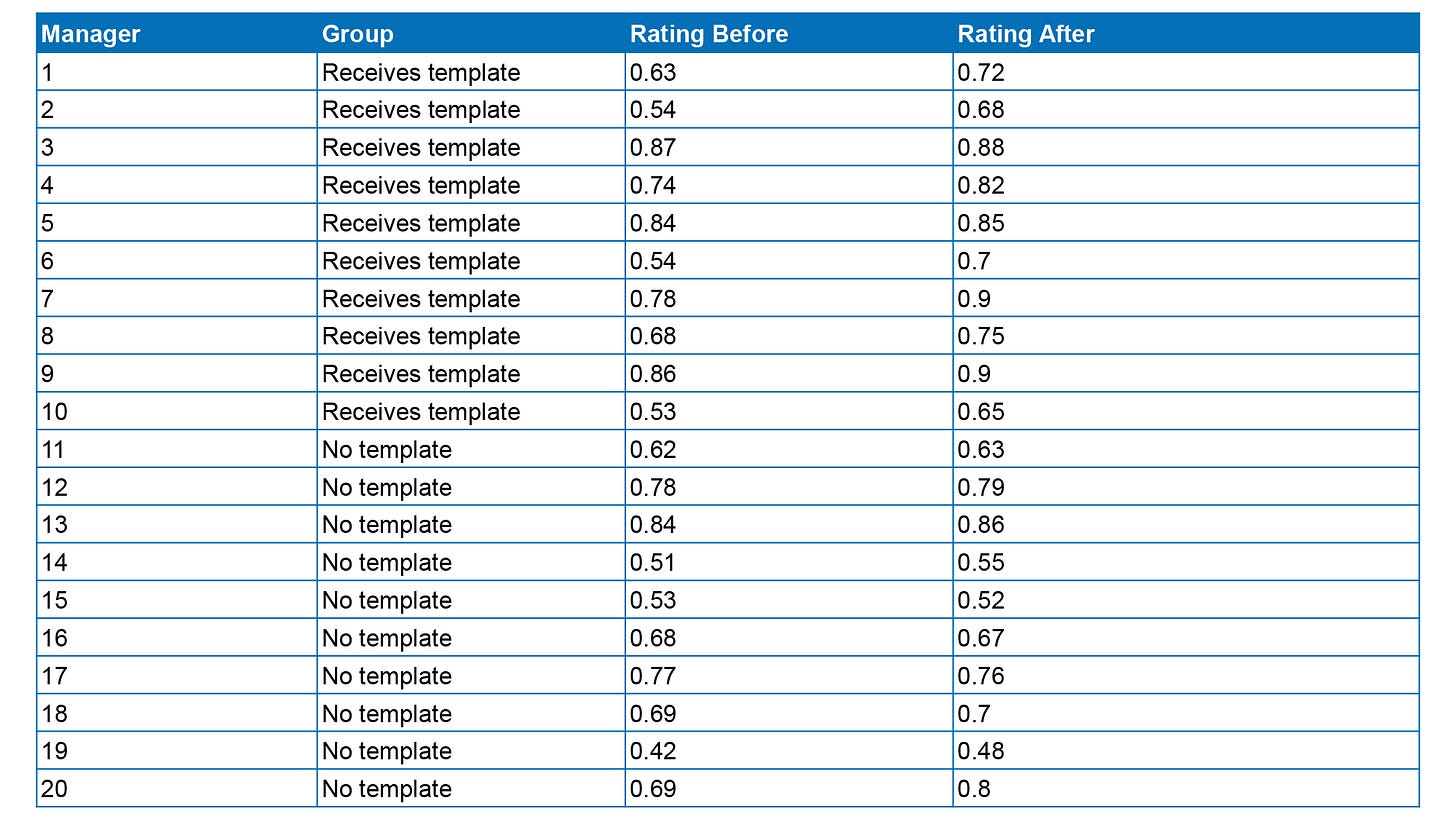

We probably have more than four managers, so let’s expand our table to show 20 (just so we have more dummy data to play with).

The analysis

So… what’s the result? Did sending the template to managers lead to better feedback conversations?

I turned to Ally and Lucy Mackay for help. Ally is 10-years-old, and Lucy is 7. Together, they were able to calculate the average (mean) rating for each group.

Here’s the results:

‘Receives template’ group:

Before: 0.7

After: 0.78

Change: +0.08

‘No template’ group:

Before: 0.65

After: 0.68

Change: +0.03

So both groups improved over the course of the experiment. We don’t know why, which is totally normal. All sorts of factors ‘in the wild’ can have an impact.

But we can point out that the managers who received the template improved more. 0.05 points more in fact!

(Worked example: 0.08 - 0.03 = 0.05, thanks Ally and Lucy!)

In other words, the managers who received the template used to score 70% for giving feedback. After receiving the template, that score increased to 78%.

Not bad! It looks like our template worked - and the only maths we needed for this analysis was carried out by children.

Wanna get fancy?

You might reasonably be thinking: How can you be sure that your feedback template, and not some other factor, made the difference? Is that improvement meaningful or not?

Setting aside the fact that the data is fictional, I wanted to use it in this newsletter to flesh out Wil’s idea that a child can do most of the analysis required by a modern learning professional.

If you’re convinced, feel free to skip down.

But if you’re face is contorted into a frown, let’s go a step further! I uploaded my dummy data to our old friend ChatGPT and asked for help. It prompted me to explain how the experiment worked, then ran the analysis.

💡 Finding 1: A Between-Group Analysis (Two-Sample T-Test) shows that the p-value is 0.00798. This is less than the alpha level of 0.05, indicating that the difference in mean changes between the Treatment (Receives template) and Control (No template) groups is statistically significant.

In other words, the result is unlikely to be due to random chance. More details here for the nerds.

💡 Finding 2: The calculated effect size, using Cohen's d, for the difference in mean changes between the Treatment and Control groups is approximately 1.33.

The effect size can be considered large. Nerds see here.

(I asked our Head of Research, Gent Ahmetaj, to check ChatGPT’s homework. All good, though he pointed out that the sample size is very small and so we should be careful about making dramatic claims.)

Conclusion

Learning analytics, learning evaluation, learning impact. It can seem difficult or intimidating. But the difficult bit isn’t the maths - it’s the need to think through problems, ask good questions and identify the data we need to measure change. It’s negotiating with stakeholders to get hold of that data, and sell the benefits of an experimental mindset.

If we can get these bits right, we can do the rest with some basic maths - and ChatGPT can help us when we get stuck.

Thanks to Andy, Wil, Gent and the #TeamMackay children for help with this post.

The Mind Tools Custom team love working on real problems, and can help you set up your own experiments. Interested? Email custom@mindtools.com or reply to this newsletter from your inbox.

🎧 On the podcast

The menopause, a natural transition that women experience, is finally becoming an open discussion topic in more communities. Does this mean that women have the understanding and support they need to thrive during this time of their lives?

While experiences vary, Jayne Saul-Paterson argues on this week’s episode of The Mind Tools L&D Podcast that the menopause is something to celebrate.

Says Jayne:

‘I think really once we’re managing our symptoms we can embrace this period of midlife. You know, it’s a time when actually we might have increased confidence and inner strength, and this can be a time to make new changes. I work with people who try out new things, who start new businesses, who decide that they do want to change careers.’

She joined Gemma and Nahdia to share her experiences and advice. You can check out the episode below. 👇

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, Spotify or the podcast page of our website. Want to share your thoughts? Get in touch @RossDickieMT, @RossGarnerMT or #MindToolsPodcast

📖 Deep dive

On the topic of learning measurement, we often hear that learning analytics can lead to better learning-design decisions. This makes intuitive sense: If we measure the impact of one instructional approach versus another, we can then identify which approach contributed to better understanding or capability.

But if you're struggling to think of a real-world example of this, you're not alone. A literature review by a team of Russian researchers found that, across 49 papers looking at the interplay of Learning Analytics (LA) and Learning Design (LD) in Higher Education (HE), an experimental approach was rare.

In 16 papers:

'The authors mentioned using LA implying it benefited LD but did not provide any specific details.'

In 18 papers:

'The studies presented specific recommendations for LD improvement but did not support them with actual evidence from practice or experiments.'

Of those papers that were explicit about the use of analytics to improve learning design, only three then measured that improvement.

If you’re interested in this area, there’s a lot of opportunity to blaze a trail!🔥

Drugova, E., Zhuravleva, I., Zakharova, U., & Latipov, A. Learning analytics driven improvements in learning design in higher education: A systematic literature review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning.

👹 Missing links

🥼 When instructions aren’t enough to overcome knowledge limitations

We’re big fans of ChatGPT here on The L&D Dispatch news desk, but this piece from Harold Jarche argues that having knowledge codified in a Large Language Model (LLM) isn’t always enough. Decades ago, PhD student Harry Collins noticed that - even with instructions - no one could get a ‘TEA laser’ to work if they hadn’t already worked in a lab that had one. Jarche points out that some forms of knowledge, like expertise and relationships, are so tied up in the ‘human’ part of any information network that they are difficult to share effectively. Hat tip to Donald H Taylor for sharing this.

🎧 It all comes back to managers

Workplace culture, values, the way we do things around here. We talk about these topics a lot here at Mind Tools. In this podcast from Mind Tools L&D Podcast alum Bruce Daisley, Professor Frances Frei makes a persuasive case that the single thing every organization should do to fix their culture is train their managers. This comes hot on the heels of the CMI report we covered, showing that 82% of managers who enter management positions have not had any formal management and leadership training.

🤓 Go to university or develop useful skills?

It’s become common to give university education a kicking. What use are the collected works of the Brontë sisters after all, when I could just learn to code in my bedroom? In this piece for The Atlantic, author (and scholar…) Ben Wildavsky points to evidence against this view, arguing that while technical skills become obsolete, ‘liberal-arts soft skills such as problem-solving and adaptability have long-term career value’. Reader, let’s hope so!

👋 And finally…

Down with ChatGPT, all hail Clippy! The only AI assistant we’ve ever needed.

👍 Thanks!

Thanks for reading The L&D Dispatch from Mind Tools! If you’d like to speak to us, work with us, or make a suggestion, you can email custom@mindtools.com.

Or just hit reply to this email!

Hey here’s a thing! If you’ve reached all the way to the end of this newsletter, then you must really love it!

Why not share that love by hitting the button below, or just forward it to a friend?