Learning equals behaviors, behaviors equal outcomes

No more tilting at the impact windmill.

Long-term readers will know that Ross D and I have long been bewildered by L&D’s existential angst over ‘impact’. Attend a conference or scroll through LinkedIn and you’ll see myriad thought leaders complaining about the lack of evidence that what we do matters.

Yet these very same thought leaders often spend their entire career in workplace learning, tilting at windmills of their own creation.

To be fair, the criticism is well intentioned. L&D does have a problem with measurement, but struggling to measure something doesn’t mean that it hasn’t worked. And, in a lot of cases, we already know what works.

In our ‘Building Better Managers’ report, published last year, we found that managers who receive support are measurably better at certain key skills:

🏈 Coaching

🥅 Goal setting

🪧 Providing guidance

👂 Active listening

❤️ Establishing trust

So what, you might ask? How do we know that being more skilled in these areas actually matters to business outcomes?

Per our recent podcast discussion, our colleague Dr Anna Barnett explains:

‘Learning doesn’t affect business outcomes directly. Learning equals behaviors, behaviors equal outcomes.

That’s what people forget.

If you jump straight to outcomes... that increase is very messy. There are too many things that influence whether... performance improves or not. It’s really, really, hard.

And this is why it becomes such a challenge to say: “did our learning work?”.’

Our goal then is to build skills in those areas where that improvement is most likely to make a measurable difference to performance. And to determine those areas, we need to do more research.

This year, we followed up on our ‘Better Managers’ report by asking 279 managers from eight countries to provide data on performance outcomes. That included percentage of sales target reached in the previous year, number of promotions on their team, and staff retention.

We then put each participant through our scientifically-validated Manager Skills Assessment.

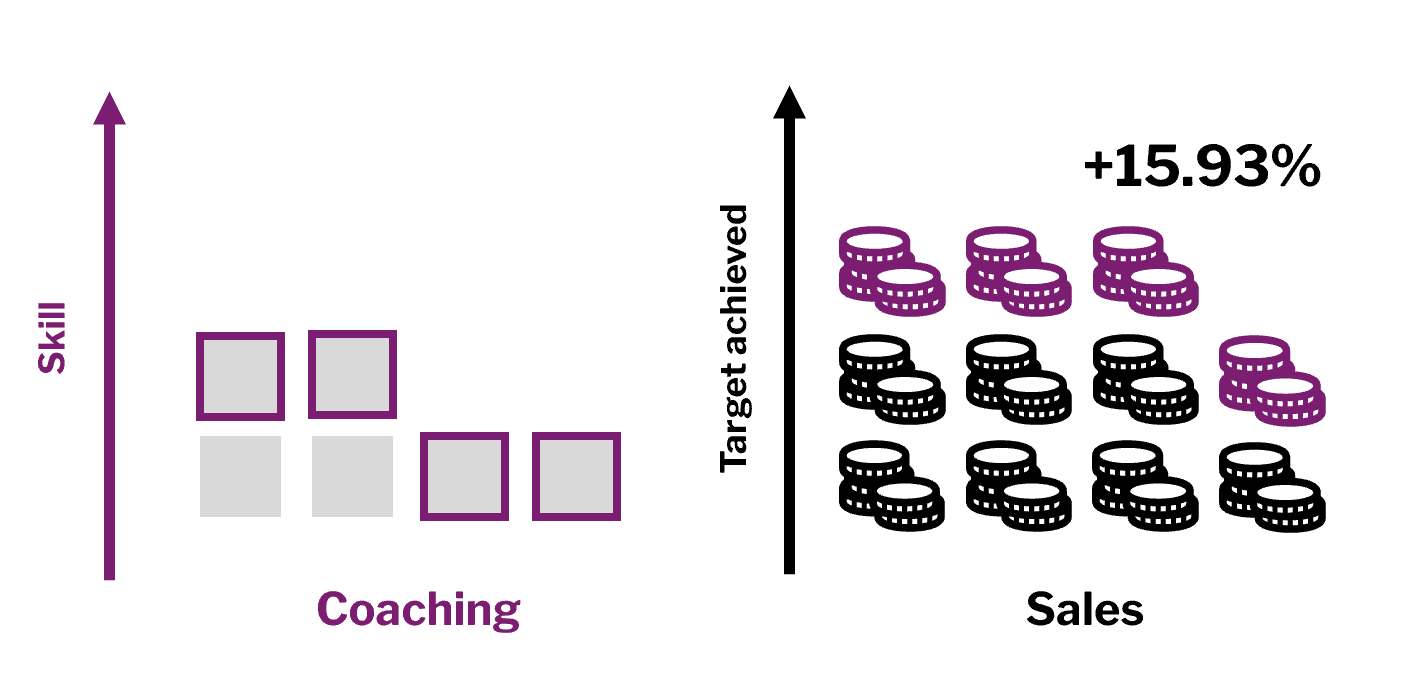

The results demonstrate a straight line from coaching skill to sales performance:

Managers who scored one point higher on our 1-6 coaching scale delivered about 16% more of their sales target, on average.

So we know that managers who receive training have better skills ✅

And we know that more skilled managers deliver better results ✅

The next question is, can we predictably build those skills?

Over the past couple of years, our Custom and Insights team have been working with Mina Papakonstantinou and the team at Deloitte to develop ‘Coaching Skills for Effective Conversations’, a blended learning program to equip everyone at the firm with the key skills required to have better professional conversations.

Within ‘coaching’, we focused on active listening, questioning, and building trust as the skills that most improve participants’ ability to influence, negotiate, build stronger relationships, win over clients and stakeholders, and lead teams.

And we measured change in skill level by using the Active Empathic Listening Scale[1], with participants completing the questionnaire before and after the program.

What we find is that participants consistently improve by an average of 15%.

At the same time, the initial skill gap between participants narrowed substantially by the end of the programme, by as much as 94%.

This means that the programme not only increased overall competency, but also helped create a more consistent skill base amongst participants - and did so consistently, across different populations.

The benefits of a long-term view

The team working on the program have done a great job. It’s won a Brandon Hall Gold award, and is a finalist at The Learning Tech Awards, Institute of Leadership Awards, and Learning Awards.

But what’s been most exciting for us is that the team has continued to measure the program over a long period of time. It means that we know the program works, and that it works predictably.

We can keep measuring the program to investigate the impact of improvements that we make, but we don’t need to worry any longer about whether it has an impact. We’ve demonstrated that it does, multiple times.

So, should you measure your own programs? I think it depends.

If you’re trying something new, or your context is particularly novel, you probably do want a sense of whether your intervention is working.

But if you’re using a tried-and-tested approach to build the skills that we know make a difference, you can be reasonably confident in the outcome that you’ll see.

As I’ve written before, every learning intervention is a bet. But you don’t need to make those bets blindly.

Want to find out more about how we can predictably deliver positive outcomes? Reply to this newsletter from your inbox or email custom@mindtools.com to schedule a chat!

[1] Drollinger, T., Comer, L. B., & Warrington, P. T. (2006). Development and validation of the active empathetic listening scale. Psychology & Marketing, 23(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20105

🎧 On the podcast

According to Donald Taylor and Egle Vinauskaitė’s recent AI in L&D: The Race for Impact report, ‘creating learning content’ and ‘learning design tasks’ remain the primary use cases for AI in learning and development. But should they be?

In this week’s episode of The Mindtools L&D Podcast, L&D consultant Heidi Kirby joins Ross D and Claire to discuss:

the obvious appeal of using AI to scale learning content;

why Heidi believes outsourcing development to AI is a mistake;

what L&D could or should be using AI for, if not content generation.

Check out the episode below. 👇

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, Spotify or the podcast page of our website.

📖 Deep dive

A nice paper this week published by our old friends at Emerald Publishing, and which I saw shared on LinkedIn by John Whitfield.

The authors set out to answer this question: Which factors in continuing professional education most affect teachers’ transfer of learning to their workplace? They focused on training design, motivation, and work environment.

In this case:

Training design refers to both how relevant the content is to the learner and how that content is presented.

Motivation refers to whether the learner both cares about the training and about applying what they learned back in the workplace.

Work environment refers to the variability, complexity, and autonomy learners experience. This one jumped out because, in my work with clients, it’s usually the factor most organizations overlook.

The study was based on a survey of 200 teachers across Texas, of whom 160 responded. The authors caution against extrapolating to other contexts.

However, within the context of this study:

Training design explains the relationship between the work environment and transfer of learning. When training is well designed, it accounts for the environment learners work in.

Learner motivation matters. Motivated learners can still transfer some learning even when training design is weak, but well-designed training amplifies that effect.

When designing your own training, ask yourself:

What are your learners trying to achieve? What do they care about?

What impact does the environment have on their ability to act on what they learned?

Is every aspect of our training relevant to the learners we’re working with?

And, if you can, ask your learners too.

Nafukho, F. M., Irby, B. J., Pashmforoosh, R., Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., Lockhart, M. E., ... & Wang, Z. (2023). Training design in mediating the relationship of participants’ motivation, work environment, and transfer of learning. European Journal of Training and Development, 47(10), 112-132.

👹 Missing links

🪴 Hyper growth or hype of growth?

What will the impact of AI be on our economy? Estimates range from 0.1% growth (meh) to 20% a year. It can be difficult to grasp the impact of these numbers so, in this blog post, Tim Harford puts these possibilities in context. At 7% growth, our economy doubles in size every decade and children end up eight times richer than their parents. Per the blog, ‘All but the most profligate governments would see their fiscal problems evaporate, the burden of the national debt vaporised by the white heat of economic growth.’ At 20% growth, a child would end up 500 times richer than their parents.

What happened when washing machines were introduced as a time saver? People washed their clothes more. What happened when email emerged as a communication tool? People communicated more. Now AI seems like the next link in that chain. In this article for HBR, the BetterUp team point to evidence that people are using AI tools to create ‘low-effort, passable looking work that ends up creating more work for their coworkers’. We can’t have nice things.

🤖 And yet, how to accelerate AI adoption

Does the above mean we should abandon AI at work? Absolutely not. But humans often need a little help demonstrating useful behaviors. In this newsletter, Peter Yang shares advice from experts on how to effectively encourage AI adoption. That includes removing bureaucratic obstacles to adoption, being specific with tactics over vague encouragement, and rewarding those who lead the charge.

The Mindtools Custom and Insights team have spent much of this year helping our clients promote safe use of organizational AI tools. Reply to this newsletter if you’d like to discuss how we can help you. Or email custom@mindtools.com.

👋 And finally…

Usually we try to find something vaguely ‘work-y’ for this segment, but today I just wanted to share something creative. Enjoy!

👍 Thanks!

Thanks for reading The L&D Dispatch from Mindtools and Kineo! If you’d like to speak to us, work with us, or make a suggestion, you can email custom@mindtools.com.

Or just hit reply to this email!

Hey here’s a thing! If you’ve reached all the way to the end of this newsletter, then you must really love it!

Why not share that love by hitting the button below, or just forward it to a friend?