Start measuring your impact today

Only 28% of L&D leaders say they have the skills needed to measure impact, but it's not as hard as it sounds.

In a recent blog post, the economist and writer Tim Harford lamented the state of statistics in ‘broken Britain’. The UK government spends £1,200bn a year (£18,000 per person) on schools, healthcare, the armed forces, policing, the courts, welfare and all sorts of other services we take for granted. Often without any idea whether that money is well spent.

Harford shares the example of the ‘National Tutoring Programme’, launched in 2020 to offset the harms of the pandemic by providing ‘high-quality tutoring in small groups’ for school pupils.

Writes Harford:

‘Yet — as the Centre for Public Data recently lamented — the DfE (Department for Education) lacked the most basic data needed to evaluate its own programme: how many disadvantaged pupils were receiving tutoring, the quality of the tutoring, and what difference it made. The National Tutoring Programme could have gathered this information from the start, collecting evidence by design. But it did not. And as a result, we are left guessing about whether or not this was money well spent.’

It’s easy to roll our eyes at government misspend, but L&D has traditionally done little better.

According to Myles Runham, Senior Analyst at Fosway Group, 73% of L&D professionals have either just started or were yet to begin ‘Measuring the impact and value add to performance and productivity’.

Our own research at Mind Tools backs this up. In 2023, only 28% of L&D leaders reported that they had the skills in-house to measure impact.

Like broken Britain, our profession regularly spends vast reams of money without any insights into whether we’re getting a meaningful return. Globally, this year alone, that spend is estimated to be US$400.94 billion.

🧐 What to do about it?

There are certain non-negotiables for most L&D teams: compliance courses, an onboarding program, some sort of management development provision. Like government spend on healthcare and schools, these programs will continue regardless.

We could measure the impact they have, but measurement is hard.

🔍 It’s hard to determine what should be measured.

📊 It’s hard to set up systematic data collection so that we can have confidence in our numbers.

🤔 And it’s hard to avoid measurement strategies that create perverse incentives.

In last week’s episode of The Mind Tools L&D Podcast, my friend-and-co-author Ross Dickie recommended a book on this very topic: Jerry Muller’s The Tyranny of Metrics.

In the book, Muller gives examples of these perversions: hospitals who avoid complicated procedures because it affects mortality rates; teachers who ‘teach to the test’ because test scores are tied to funding.

And he describes where measurement most often goes wrong.

🤯 Where measurement goes wrong

Here’s how Ross D tells it in the podcast:

‘The first one is measuring the most easily measurable. This is something you see in L&D quite a lot, where people will typically measure engagement [or] completion.

‘Measuring inputs, not outcomes. For example, it'd be really easy to deliver return on investment by taking a face-to-face leadership program and converting it all to e-learning. “This has saved the organization tons of money!” But if you're not looking at the output and the outcomes of that, you're not really getting a full sense of the impact that it's having.

‘And then degrading information quality through standardization, which allows easy comparison but strips individuals of context while creating an illusion of certainty.’

These are certainly dangers to be aware of. But I can’t help but feel that they are more of an issue in domains where data collection in rampant.

In L&D, as I wrote at the outset of this piece, data collection is often superficial or nonexistent.

You might be reading this then and thinking: ‘Well, why bother? I’m damned if I measure and damned if I don’t.’

But that’s the wrong conclusion.

🤯 Getting started with measurement

Measuring attendance is a relatively superficial metric. In fact, it’s the bottom tier of Will Thalheimer’s Learning Transfer Evaluation Model. But, if no one is attending your workshop or taking your course, it’s difficult to argue that either of those things is having any impact at all.

Measuring inputs isn’t bad, in-and-of itself. Financial savings are a good thing. You just want to combine measurement of inputs with some attempt at measuring output.

And standardization is helpful for drawing conclusions, so long as we acknowledge the uncertainty that exists within those conclusions and interpret those results within their context.

L&D will not get better at measurement by fleeing from this challenge.

🤯 A quick example

We recently deployed 12 new ‘Skill Bites’ courses to our Mind Tools platform. As we’ve written before, each course targets one of the 12 capabilities that we know through research makes a difference to manager performance. And each Skill Bite offers a self-assessment, followed by regular spaced practice over a period of weeks.

Now that they’ve launched, we’ve kicked off a new project to measure their value to our users/learners.

That starts with attendance. A user who engages with the second session probably found value in the first. Where users don’t return, attendance tells us that the first week wasn’t that useful.

Insight #1: The first visit tells you if your marketing activities worked. The second tells you whether users wanted to come back.

During each Skill Bites session, we ask users to record a written commitment. If they do this, it tells us that they had enough support within the content to feel confident doing so. If not, we need to revisit our scaffolding (or, the guidance we provide in the form of instructions and examples).

Insight #2: Asking learners to create something is a great way to prompt them to reflect on how they will apply what they have learned.

The following week, we follow up on their commitment. Did they achieve it, yes or no? That’s an output that tells us whether what they have learned is making a difference to how they perform at work.

Insight #3: Follow-up surveys don’t need to be complicated. This one question tells us whether learner behavior is starting to change.

And then we can standardize our data across the entire Skill Bites collection to assess the relative performance of each. But, with context: We don’t actually want every user to complete every commitment. That would suggest the commitments are too easy and may not be meaningful.

Instead, we want to vary the difficulty of the challenges that users are set and look at the relationship between weekly commitments and ongoing participation in the course.

Insight #4: Comparisons are useful, but we need to understand what we’re comparing and the behavior that we want to see.

All of this comes from a tiny dataset:

# of users who start a session

# of users who achieved their previous commitment

# of users who did not achieve their previous commitment

# of users who made a new commitment

# of users who completed the session

Five numbers per session. But, from these, we can infer a lot that informs how we improve the product, and how we better develop our learners.

🤯 A final thought

And remember, as Harford writes about ‘Broken Britain’, there’s a cost to not measuring what you’re doing. There's the financial cost of spending money in the wrong place; the waste involved in spending money on initiatives that don't work; and the opportunity cost for colleagues and users - the people we serve - whose performance at work does not improve because we didn't support them as well as we could.

This week, take a look at what you’re already measuring, and what you wish you could measure. What is the size of that gap, and what’s one thing you could do right now to help close it?

No idea where to start? Ross D and I are always happy to have a chat, with no obligation that you then work with us. Get in touch by emailing custom@mindtools.com or reply to this newsletter from your inbox to arrange a time.

🎧 On the podcast

While I was on holiday last week, Ross D recorded a podcast with our colleagues Nahdia Khan and Owen Ferguson, where they shared their summer reading recommendations.

As well as The Tyranny of Metrics discussed above, the team shared their thoughts on Amy Edmondson’s new book Right Kind of Wrong: Why Learning to Fail Can Teach Us to Thrive, and A History of the World in Twelve Shipwrecks

Listening to the episode, I was relieved that they didn’t recommend my own recent science fiction debut, Centauri’s Shadow.

While it’s currently rated 4.9 out of 5 on Amazon UK, and 4.8 out of 5 on Amazon US, it spared me the embarassment of being included in their list and avoided any accusation that I was using the Mind Tools brand to promote my personal project, no matter how ‘compulsively readable’ it may have been described as by one reviewer.

Check out the episode below. 👇

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, Spotify or the podcast page of our website. Want to share your thoughts? Get in touch @RossDickieMT, @RossGarnerMT or #MindToolsPodcast

📖 Deep dive

Back in November 2022, our friend Jane Bozarth from the Learning Guild joined us on The Mind Tools L&D Podcast to discuss three papers that challenge well-known but squiffy ideas. One of these ideas, that how children perform in the ‘marshmallow test’ can predict long-term life outcomes, was the focus of our very first ‘Deep Dive’ segment!

A quick primer for those of you who didn’t subscribe to The L&D Dispatch from day one (shame on you!):

Back in the 1960s, Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel set up an experiment where he would place a marshmallow in front of a child — and promise a second marshmallow if the child could go 15 minutes without eating the first.

In the 1990s, Mischel then checked in with these children to see how they had fared in life. Those who had a waited for the second marshmallow, or had ‘delayed gratification’, tended to have performed better academically and coped better with stress.

The ‘Marshmallow Test’ became famous and led to many programs designed to improve the ability of children to self-regulate. The central idea being that, if we can teach children to wait for the second marshmallow, they are likely to have better long-term life outcomes.

Then, in 2018, Tyler Watts from NYU, along with Greg Duncan and Haonan Quan from UC Irvine, published a follow-up paper that attempted to replicate the original finding, while correcting for issues with the original study. Journalist Jessica McCrory Calarco described these corrections in a piece for The Atlantic at the time:

‘The researchers used a sample that was much larger—more than 900 children—and also more representative of the general population in terms of race, ethnicity, and parents’ education. The researchers also, when analyzing their test’s results, controlled for certain factors—such as the income of a child’s household—that might explain children’s ability to delay gratification and their long-term success.’

What that 2018 paper found was that a child’s home environment had far more impact on their long-term outcomes than their ability to resist the temptation of eating a marshmallow.

⏰ Taking us up to the present

Now a new paper from researchers at Columbia University and the University of California has explored the association between the performance of children taking part in the Marshmallow Test and their outcomes at the age of 26.

This time, the researchers looked at educational attainment, annual earnings, body mass index, depression, drug use, risk-taking behaviors, impulse control, police contact and debt.

The only relationship the researchers found was with educational attainment and BMI, which then became statistically nonsignificant once early home environment was factored in.

💡 Why does any of this matter?

The researchers conclude:

‘These results suggest that an intervention narrowly targeting delay of gratification abilities are unlikely to produce long-term effects, unless subsequent changes are also made to other aspects of the child's environment and/or characteristics.’

Put simply: Teaching a child to wait before eating a marshmallow doesn't have an impact on long-term outcomes. Increasing the likelihood of them being fed regularly at home does.

Sperber, J. F., Vandell, D. L., Duncan, G. J., & Watts, T. W. (2024). Delay of gratification and adult outcomes: The Marshmallow Test does not reliably predict adult functioning. Child Development.

👹 Missing links

Last week, former Nike executive Massimo Giunco took to LinkedIn to explain the company’s 30% drop in value in the past year with the headline: ‘Nike: An Epic Saga of Value Destruction’. According to Giunco, the issues stem from the elimination of categories (Basketball, Running, etc), de-prioritization of their wholesale business in favor of direct-to-consumer, and a heavy focus on digital marketing with an emphasis on serving existing customers rather than creating new ones.

There’s likely some bias here. Giunco is a brand strategist who didn’t like the downturn in Nike’s brand building activities. But this line jumped out for obvious reasons:

‘Nike invested a material amount of dollars (billions) into something that was less effective but easier to be measured vs something that was more effective but less easy to be measured.’

The tyranny of metrics indeed! Hat tip to Trung Phan’s excellent newsletter for this one.

🤖 This AI friend has you by the throat

If you’re feeling lonely, how would you like an AI necklace that will chat to you whenever you want? The device, which sells for $99 and is called ‘Friend’, listens to you all the time and will either respond when spoken to or proactively send you a message.

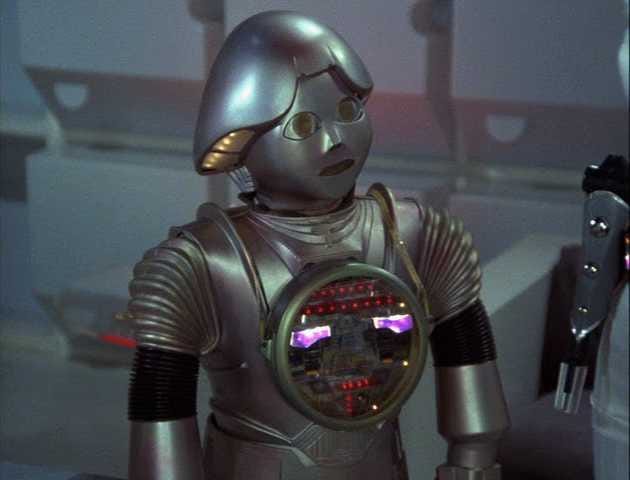

I’m not sure it’s for me, but I immediately recognized yet another example of life imitating art. Remember Dr Theopolis, the robot necklace carried around by Twiki in Buck Rogers in the 25th Century? No? Just me?

👋 And finally…

All this talk of marshmallows, man… It reminds me of this banger, from a time when big summer blockbusters came with a hit single, celebrity cameos and wall-to-wall merch. Enjoy!

👍 Thanks!

Thanks for reading The L&D Dispatch from Mind Tools! If you’d like to speak to us, work with us, or make a suggestion, you can email custom@mindtools.com.

Or just hit reply to this email!

Hey here’s a thing! If you’ve reached all the way to the end of this newsletter, then you must really love it!

Why not share that love by hitting the button below, or just forward it to a friend?